"That was possible because Bonestell had traveled out into space ahead of everyone else—and he took his paintbrush with him. He orbited the Earth before Gagarin and Glenn, left his footprints on the dusty lunar surface before Neil Armstrong, viewed a Martian sunset before the Viking probes landed there, and explored Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune before the Voyagers ever visited those giant, gaseous planets." — A Chesley Bonestell Space Art Chronology Melvin H. Schuetz, 1999 [15]

When Trouvelot and Rudaux created their images, they did so with an eye on the technical aspect of their subject; that is, their work was created for scientific purposes as opposed to artistic offerings, though both were accomplished artisans in their own right. Others, like Butler, developed their own style by combining the realism of the subject matter to an artistic what if, thereby stirring one's imagination with images like that of the Earth as it would appear to someone standing on our Moon, a painting rendered by Butler and displayed for years at the the old Hayden Planetarium. As for Chesley Bonestell, his work went much further then just a fusion of art and science. His images were a deliberate merging of technical elements, artistic style and a successful collaboration that carried within it a clearly rendered visionary element — the possibility of space travel. Though Schneeman, and others before him had successfully achieved an incorporation of known scientific knowledge into their own art, Bonestell was able to take it many steps further, thereby creating visually stunning images and a conceptual awareness for the proposition of manned space travel, inspiring the very individuals who would make journeying into outer space and beyond possible. Image of Chesley Bonestell courtesy NASA

When Trouvelot and Rudaux created their images, they did so with an eye on the technical aspect of their subject; that is, their work was created for scientific purposes as opposed to artistic offerings, though both were accomplished artisans in their own right. Others, like Butler, developed their own style by combining the realism of the subject matter to an artistic what if, thereby stirring one's imagination with images like that of the Earth as it would appear to someone standing on our Moon, a painting rendered by Butler and displayed for years at the the old Hayden Planetarium. As for Chesley Bonestell, his work went much further then just a fusion of art and science. His images were a deliberate merging of technical elements, artistic style and a successful collaboration that carried within it a clearly rendered visionary element — the possibility of space travel. Though Schneeman, and others before him had successfully achieved an incorporation of known scientific knowledge into their own art, Bonestell was able to take it many steps further, thereby creating visually stunning images and a conceptual awareness for the proposition of manned space travel, inspiring the very individuals who would make journeying into outer space and beyond possible. Image of Chesley Bonestell courtesy NASABonestell was born in 1888, in the city of San Francisco, California. Like many others before and after him, his interest in astronomy was aroused not from the academic field but from hands-on experience, viewing the moon and the planet Saturn in 1905 through the 12-inch telescope at the Lick Observatory in San Jose California. Inspired and excited, Bonestell created his first painting of what he had viewed through the observatory's telescope, a rendering which was unfortunately destroyed the following year in the large fire that resulted from the earthquake which rocked San Francisco and other cities in 1906.

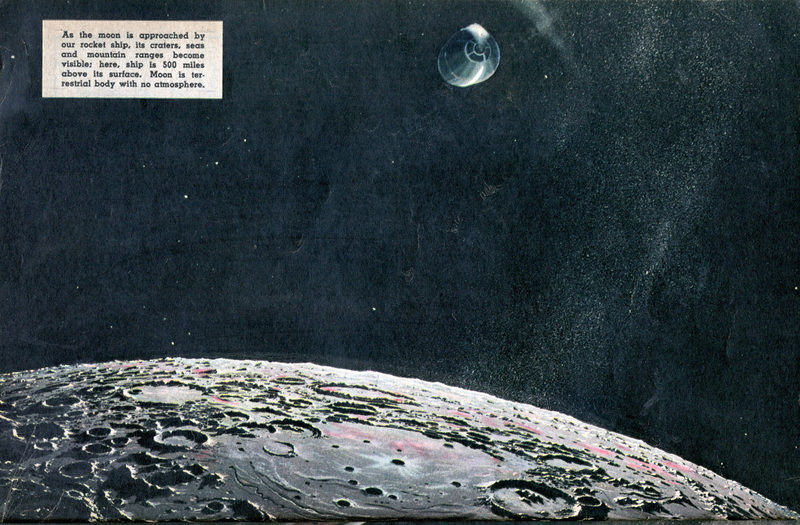

Though Bonestell's astronomical pursuits began early on, it would be his artistic and drawing abilities that would start his long career. He began his higher educational studies in architecture, at Columbia University in New York City, a discipline that he actually enjoyed, applying himself to the extent that he bacame a master at the art of perspective drawing. After three of years of study, Bonestell chose to leave the university without graduating, eventually returning to San Francisco where, finding himself well qualified, he obtained work as a designer for the well known architect Willis Polk. By 1916, Bonestell had moved on to other projects, obtaining a position as designer in collaboration with California landscape architecture Mark Daniels, lending his talents in the creation of the world-renowned 17-mile drive in Pebble Beach, California. It was during this period that his interests again turned towards the science of astronomy, applying his artistic talents in a variety of images depicting the surface of the Moon and the planet Mars.

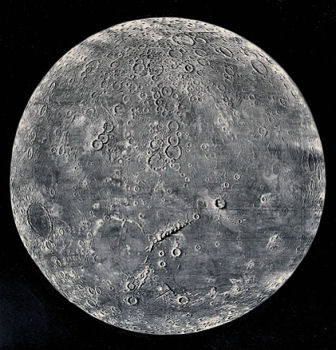

In 1920 Bonestell, having divorced his first wife Mary Hilton, moved back to New York where he once again took up work for various architectural firms. It was during this period that Bonestell met the 5-foot 3-inch tall world famous lady tenor from Bristol, Ruby Helder, deciding shortly thereafter to move to England with her where the two were married at the St Marylebone Register Office on July 12, 1920. While in England, Bonestell was employed by the Illustrated London News in the field which he had so far been successful, architectural illustrations. It was during his time in England that Bonestell came into contact with the work of two early illustrators of space art, Scriven Bolton and the previously mention Lucien Rudaux. Bolton, an artist also working for the Illustrated London News, had used a unique technique for his illustrations developed earlier by James Nasmyth and James Carpenter for their book The Moon [fn1] which involved the use of plaster models to represent a planetary surface, a correct lighting arrangment and a black backdrop, complete with stars. Bonestell would later use a similar method when working on various film projects in Hollywood. At right is an image entitled Picture Map of the Moon from the 1885 publication The moon by James Nasmyth and James Carpenter. [16]

In 1920 Bonestell, having divorced his first wife Mary Hilton, moved back to New York where he once again took up work for various architectural firms. It was during this period that Bonestell met the 5-foot 3-inch tall world famous lady tenor from Bristol, Ruby Helder, deciding shortly thereafter to move to England with her where the two were married at the St Marylebone Register Office on July 12, 1920. While in England, Bonestell was employed by the Illustrated London News in the field which he had so far been successful, architectural illustrations. It was during his time in England that Bonestell came into contact with the work of two early illustrators of space art, Scriven Bolton and the previously mention Lucien Rudaux. Bolton, an artist also working for the Illustrated London News, had used a unique technique for his illustrations developed earlier by James Nasmyth and James Carpenter for their book The Moon [fn1] which involved the use of plaster models to represent a planetary surface, a correct lighting arrangment and a black backdrop, complete with stars. Bonestell would later use a similar method when working on various film projects in Hollywood. At right is an image entitled Picture Map of the Moon from the 1885 publication The moon by James Nasmyth and James Carpenter. [16]After visting Italy in 1925 the Bonestells returned to England but decided to return to New York in 1927 as a result of the employment opportunities afforded Bonestell fom the sudden growth in hi-rise building construction. There, Bonestell was again employed as a designer with several well known architectural firms but the sudden demise of the stock market in 1929 saw his return to the San Francisco area where he was employed creating illustrations depicting the various phases of construction on the Golden Gate Bridge.

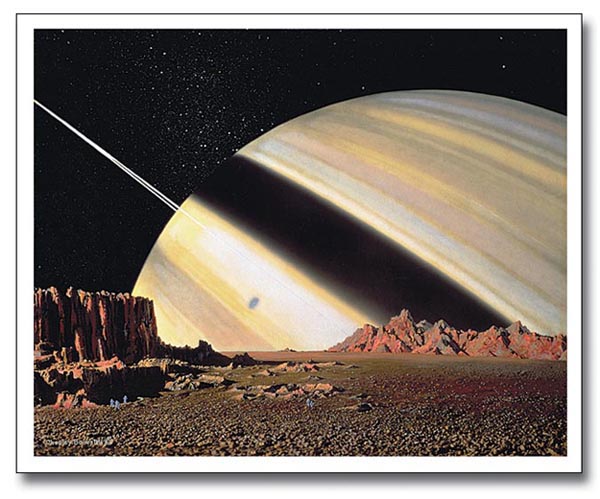

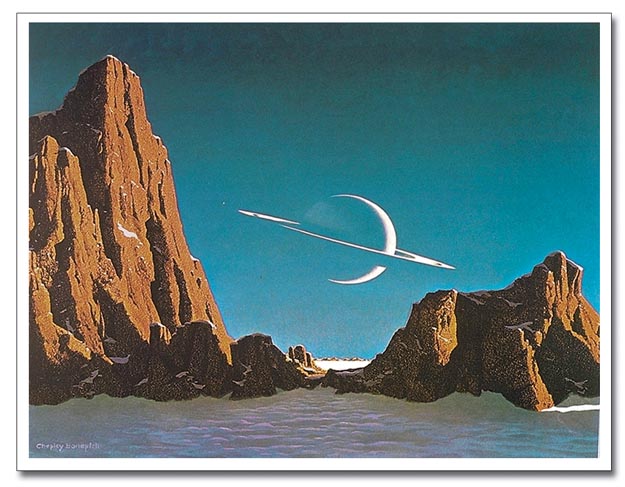

In 1938 Chelsey Bonestell changed careers, seeking and gaining employment as a matte artist in Hollywood for production studios RKO, MGM, Fox, Columbia, Paramount and Warner Brothers, his work appearing in such movies as The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Citizen Kane, Destination Moon as well as many others. At the start of his studio work his wife Ruby died and in 1940 he remarried his first wife, Mary Hilton. Continuing his work in Hollywood, Bonestell began to accquire an increased knowledge regarding the rendering of objects as they would be viewed from changing angles, such as one would see if in actual flight. With this aspect added to his artistic abilities, Bonestell painted a series of images of Saturn as it would be viewed from five of its moons and submitted them to Life magazine, who bought and published his paintings in their May, 1944 issue. The images not only amazed the professionals and public at large they also ushered in a new era of space art, their style and content a new approach to the visulization of astronomical science. Shown at left is one of the several influential and powerful vistas painted by Bonestell, a view of Saturn as Seen from Mimas, and published in Life Magazine in 1944. Painting Courtesy Novaspace Galleries

In 1938 Chelsey Bonestell changed careers, seeking and gaining employment as a matte artist in Hollywood for production studios RKO, MGM, Fox, Columbia, Paramount and Warner Brothers, his work appearing in such movies as The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Citizen Kane, Destination Moon as well as many others. At the start of his studio work his wife Ruby died and in 1940 he remarried his first wife, Mary Hilton. Continuing his work in Hollywood, Bonestell began to accquire an increased knowledge regarding the rendering of objects as they would be viewed from changing angles, such as one would see if in actual flight. With this aspect added to his artistic abilities, Bonestell painted a series of images of Saturn as it would be viewed from five of its moons and submitted them to Life magazine, who bought and published his paintings in their May, 1944 issue. The images not only amazed the professionals and public at large they also ushered in a new era of space art, their style and content a new approach to the visulization of astronomical science. Shown at left is one of the several influential and powerful vistas painted by Bonestell, a view of Saturn as Seen from Mimas, and published in Life Magazine in 1944. Painting Courtesy Novaspace GalleriesWith the surrender of the Axis in 1945, World War Two came to a close, but in its wake it left a legacy of change: the atomic bomb, jet fighters, the United Nations, the Berlin Wall, the reshaping of Europe, television, baby boomers and the computer. It also brought an impetus for developement into a new age of technology that was soon to turn into a contest between two of the era's most powerful nations; a contest began in fear and enmity, developed out of the political agenda of the times to become one of the most strived for national goals ever — the "Age of Rockets" and the "Race for Space" had arrived.

Footnote

1. Notes David A. Hardy in his article THE HISTORY OF ASTRONOMICAL ART AND THE IAAA (The Electronic Astrobiology Newsletter Volume 6, Number 31, 1 October 1999) "In 1874 a book was published in England entitled simply The Moon, by James Nasmyth and James Carpenter. Nasmyth created accurate plaster models of the Moon's surface, lit them correctly and photographed them against a starry, black background as illustrations. These are probably the first examples of true space art."

Since there had been little public interest in the United States at the time Ley arrived, he continued to write articles and books publicizing the practicality of manned spaceflight in the relatively near future while maintaining employment in areas other than the science of rocketry. He worked as a science editor at the New York newspaper PM until 1944 and afterwards, moved to the Washington Institute of Technology in College Park, MD to work as a research engineer. However, when German launched V-2 missles began falling on London in 1944, Ley was sought out as a knowledgable adviser on rocketry. It was also the yeat that he published a new and most insightful book under the title Rockets: the Future of Travel Beyond the Stratosphere (the title was revised to Rockets, Missiles, and Space Travel for its 2nd publication and Rockets, Missiles, and Men in Space in its 3rd edition). This book expressed Ley's "belief that rockets would soon be able to carry humans into space, perhaps even to the Moon. This was one of the earliest books on rocketry for the general American public, and served as a basic reference source for future science fiction and reality writing." At right is an image showig a Peenemünde Museum replica V-2 rocket, courtesy original author at

Since there had been little public interest in the United States at the time Ley arrived, he continued to write articles and books publicizing the practicality of manned spaceflight in the relatively near future while maintaining employment in areas other than the science of rocketry. He worked as a science editor at the New York newspaper PM until 1944 and afterwards, moved to the Washington Institute of Technology in College Park, MD to work as a research engineer. However, when German launched V-2 missles began falling on London in 1944, Ley was sought out as a knowledgable adviser on rocketry. It was also the yeat that he published a new and most insightful book under the title Rockets: the Future of Travel Beyond the Stratosphere (the title was revised to Rockets, Missiles, and Space Travel for its 2nd publication and Rockets, Missiles, and Men in Space in its 3rd edition). This book expressed Ley's "belief that rockets would soon be able to carry humans into space, perhaps even to the Moon. This was one of the earliest books on rocketry for the general American public, and served as a basic reference source for future science fiction and reality writing." At right is an image showig a Peenemünde Museum replica V-2 rocket, courtesy original author at  If Bonestell's collaboration with the well known architects of his day had been successful, his collaboration with the scientists of rocketry would be even more so. Shortly after being introduced to Willy Ley, Bonestell began a series of images that incorporated Ley's own belief and technical expertise in the idea that manned space travel was close at hand, as indeed it was — on April 12, 1961, a Vostok rocket launched a

If Bonestell's collaboration with the well known architects of his day had been successful, his collaboration with the scientists of rocketry would be even more so. Shortly after being introduced to Willy Ley, Bonestell began a series of images that incorporated Ley's own belief and technical expertise in the idea that manned space travel was close at hand, as indeed it was — on April 12, 1961, a Vostok rocket launched a  In Life's March 4, 1946 issue Bonestell, in collaboration with Ley, published an article with illustrations on manned space travel to the Moon that later inspired the movie Destination Moon by

In Life's March 4, 1946 issue Bonestell, in collaboration with Ley, published an article with illustrations on manned space travel to the Moon that later inspired the movie Destination Moon by

Prior to Life's 1946 release, Bonestell, Ley and the

Prior to Life's 1946 release, Bonestell, Ley and the

The

The

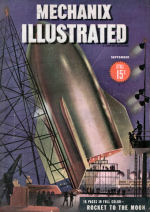

Written beneath the front cover's image is the bold and promising message proclaiming the book to be "A preview of the greatest adventure awaiting mankind with text and pictures based on the latest scientific research" As the readers of this book were to discover, it was exactly that and a whole lot more.

Written beneath the front cover's image is the bold and promising message proclaiming the book to be "A preview of the greatest adventure awaiting mankind with text and pictures based on the latest scientific research" As the readers of this book were to discover, it was exactly that and a whole lot more.