Chapter One

Dangerous Concept, Dangerous Times: Galileo, Kepler and the Church

Page 2"I much prefer the sharpest criticism of a single intelligent man to the thoughtless approval of the masses." — Johannes Kepler, German Astronomer 1571-1630

Galileo's Telescope, a Practical and Innovated Instrument In May of 1609, Galileo had either received a letter from Paolo Sarpi or heard during his everyday business affairs, about a spyglass device that a Dutchman (Fleming) had shown to him in Venice. Regardless of how the news eventually reached Galileo, he set out to create a working model based only on the description given him. But the road to discovery and fame does not always start where one wishes and Galileo's path began with a need to employ or sell his device for other purposes. "Galileo had business commitments designing and manufacturing military and scientific instruments." As Lippershey had done when he sold his device to the Dutch army, who's interest in it was to view and estimate the size of an advancing force, so too did Galileo perceive the usefulness of the device and its advantage for a more earthly purpose. Shown at left is the 17th Century Map by Johannes Kepler, that was included, along with other works, in his publication entitled Rudolphine Tables (1627). [1]

In May of 1609, Galileo had either received a letter from Paolo Sarpi or heard during his everyday business affairs, about a spyglass device that a Dutchman (Fleming) had shown to him in Venice. Regardless of how the news eventually reached Galileo, he set out to create a working model based only on the description given him. But the road to discovery and fame does not always start where one wishes and Galileo's path began with a need to employ or sell his device for other purposes. "Galileo had business commitments designing and manufacturing military and scientific instruments." As Lippershey had done when he sold his device to the Dutch army, who's interest in it was to view and estimate the size of an advancing force, so too did Galileo perceive the usefulness of the device and its advantage for a more earthly purpose. Shown at left is the 17th Century Map by Johannes Kepler, that was included, along with other works, in his publication entitled Rudolphine Tables (1627). [1]

The initially enthusiastic reception of the telescope had nothing to do with observation of the skies, but rather revolved around the ability to see terrestrial objects. Galileo heard of the Dutch telescope while a professor at the University of Padua, which was part of the Republic of Venice. The Venetians realized the great value of the telescope for their merchant fleet as well as for use on dry land, and the State Council therefore encouraged and supported Galileo to continue his investigations and to develop his own telescope. At left is an image of Paolo Sarpi by George Vertue (1684—1756) courtesy Wikipedia [2]

In a letter written to his brother-in-law Benedetto Landucci, Galileo relates the events that occurred after he discovered a way to reproduce his own version of the new invention:

"...I set about thinking how to make it, and at length I found out, and have succeeded so well that the one I have made is far superior to the Dutch telescope. It was reported in Venice that I had made one, and a week since I was commanded to show it to his Serenity and to all the members of the Senate, to their infinite amazement. Many gentlemen and senators, even the oldest, have ascended at various times the highest bell-towers in Venice, to spy out ships at sea making sail for the mouth of the harbor, and have seen them clearly, though without my telescope they would have been invisible for more than two hours. The effect of this instrument is to show an object at a distance of, say fifty miles, as if it were but five miles off.

"...I set about thinking how to make it, and at length I found out, and have succeeded so well that the one I have made is far superior to the Dutch telescope. It was reported in Venice that I had made one, and a week since I was commanded to show it to his Serenity and to all the members of the Senate, to their infinite amazement. Many gentlemen and senators, even the oldest, have ascended at various times the highest bell-towers in Venice, to spy out ships at sea making sail for the mouth of the harbor, and have seen them clearly, though without my telescope they would have been invisible for more than two hours. The effect of this instrument is to show an object at a distance of, say fifty miles, as if it were but five miles off.

Perceiving of what great utility such an instrument would prove in naval and military operations, and seeing that his Serenity greatly desired to possess it, I resolved four days ago to go to the palace and present it to the Doge as a free gift. And on quitting the presence-chamber I was commanded to bide awhile in the hall of the Senate, whereunto, after a little, the Illustrissimo Prioli, who is Procurator and one of the Riformatori of the University, came forth to me from the presence-chamber, and, taking me by the hand, said that the Senate, knowing the manner in which I had served it for seventeen years at Padua, and being sensible of my courtesy in making it a present of my telescope, had immediately ordered the Illuseiectedto the trious Riformatori to elect me...to the professorship for life, with a...stipend of 1,000 florins year." At left is the 1624 portrait of Galileo Galilei by Ottavio Leoni (1578-1630), courtesy Wikipedia. [3]

Galileo was obviously aware of the practical uses for his new device; the tangible aspects of advancement, money and perhaps the fame that it could bring. Indeed, his research and work for the Venetians, who supported his efforts at this time, were intended as a means of furthering his salary and standing. However, this never bore fruit and the two seemed to have had a falling out for fiscal reasons. As noted in an article from the School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland entitled Galileo Galilei:

He kept Sarpi informed of his progress and Sarpi arranged a demonstration for the Venetian Senate. They were very impressed and, in return for a large increase in his salary, Galileo gave the sole rights for the manufacture of telescopes to the Venetian Senate. It seems a particularly good move on his part since he must have known that such rights were meaningless, particularly since he always acknowledged that the telescope was not his invention!

The Venetian Senate, perhaps realising that the rights to manufacture telescopes that Galileo had given them were worthless, froze his salary. However he had succeeded in impressing Cosimo and, in June 1610, only a month after his famous little book was published, Galileo resigned his post at Padua and became Chief Mathematician at the University of Pisa (without any teaching duties) and 'Mathematician and Philosopher' to the Grand Duke of Tuscany. In 1611 he visited Rome where he was treated as a leading celebrity; the Collegio Romano put on a grand dinner with speeches to honour Galileo's remarkable discoveries. He was also made a member of the Accademia dei Lincei (in fact the sixth member) and this was an honour which was especially important to Galileo who signed himself 'Galileo Galilei Linceo' from this time on. [4]

Advancement

O telescope, instrument of knowledge, more precious than any sceptre. — Johannes Kepler, in a letter to Galileo (1610)

Galileo Looks to Move On For Galileo, the telescope represented something far more important - advancement and the means of escaping the confines and responsibilities required of him while at the University of Padua. This was not a new desire, for Galileo had earlier drawn the correct and sombering truth of his position at Padua and expressed such when he wrote, in a letter to one Vespuccio of Florence:

For Galileo, the telescope represented something far more important - advancement and the means of escaping the confines and responsibilities required of him while at the University of Padua. This was not a new desire, for Galileo had earlier drawn the correct and sombering truth of his position at Padua and expressed such when he wrote, in a letter to one Vespuccio of Florence:"It is impossible to obtain from a republic, however splendid and generous, a stipend without duties attached to it ; for to have anything from the public one must work for the public, and as long as I am capable of lecturing and writing, the Republic cannot hold me exempt from duty, while I enjoy the emolument. In short, I have no hope of enjoying such ease and leisure as are necessary to me, except in the service of an absolute prince." [5]

Galileo, now forty-five years of age had been longing for the home in his heart, Florence. However, something and someone was needed in order to secure his future there or anywhere and Gailieo knew this. He had already discussed this and other points in a letter to his friend Vespuccio, indicating that he continued to "discovered things daily", was busy not only with his lectureship but with the giving of private lessons as well, all in an effort to maintain a decent standard of living; Galileo was beginning to feel trapped in his current position. His letter to Vespuccio may also have intended to lay the foundations for a move to Florence however, Galileo was in no position to pick and choose, having nothing in hand to offer at that time and as such, his desires needed to be kept secret a while longer:

"Thus succinctly, most gentle Signor Vespuccio, have I laid before you my thoughts. Whenever you see a fit opportunity for doing so, I would beg you to make the illustrious Signori Eneas and Silvio acquainted with the same. I know that I can thoroughly depend on the friendship of these two, and I shall have recourse to none besides. I therefore beg your lordship not to communicate the contents of this letter to any but these gentlemen." [6]

That something finally arrived, in the form of the new invention then spreading across the European continent - the telescope. Of course, being Galileo, a man who's life had till that time been devoted to the "working science of things" (one will remember that he was a "most respected instrument maker") it would have been out of character for him not to have employed the telescope for more than just tangible gain, and so he did. In 1609, in Padua, Galileo pointed his telescope towards the Moon, thus becoming the first to employ the new instrument to observe and document the celestial object. At left are seen a pair of refracting telescopes owned by Galileo courtesy © WGBH/NOVA website.

That something finally arrived, in the form of the new invention then spreading across the European continent - the telescope. Of course, being Galileo, a man who's life had till that time been devoted to the "working science of things" (one will remember that he was a "most respected instrument maker") it would have been out of character for him not to have employed the telescope for more than just tangible gain, and so he did. In 1609, in Padua, Galileo pointed his telescope towards the Moon, thus becoming the first to employ the new instrument to observe and document the celestial object. At left are seen a pair of refracting telescopes owned by Galileo courtesy © WGBH/NOVA website.Galileo's star was about to rise to the highest echelons within the european scientific community and over the next twenty years, 1610-1630, his life, livelihood and character would change. Yet, at the same time, Galileo's ascent would manage to bring together, for better or worse, two separate and divergent trains of thought, scientific and spirtual, to the point of historic confrontation, causing a rift between science and religion that would last well into the 20th century.

From within the Venetian senate came a handsome order for Galileo to supply the arsenal with spyglasses. Galileo was given a generous lifetime salary for his service to the republic. Part scientist and part self-promoter, for now, his future seemed bright. But soon his telescope would launch a dispute which would threaten to destroy its creator. [7]

From within the Venetian senate came a handsome order for Galileo to supply the arsenal with spyglasses. Galileo was given a generous lifetime salary for his service to the republic. Part scientist and part self-promoter, for now, his future seemed bright. But soon his telescope would launch a dispute which would threaten to destroy its creator. [7]

"non est ad astra mollis e terris via" — there is no easy way from the earth to the stars

Lucius Annaeus Seneca (c. 4 BC—AD 65) Image: Luca Giordano, The death of Seneca (1684)

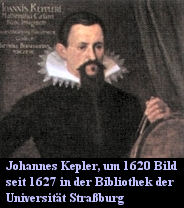

Meanwhile, in the early part of 1609, a comtemporary of Galileo was making his own mark on science. In that year a German named Johannes Kepler published a work under the title New Astronomy, and within its pages were Kepler's first two laws of planetary motion (the thrid would not arrive until 1618). Over the succeeding years, both men would independantly pursue research (though Kepler's theoretical work at this time was ahead of Galileo's) that would eventual become the foundations that merged much of the scientific knowledge up to that time into modern theoretical and physical astronomy. Who was Johannes Kepler and what were his contribution to science are the subjects of our next chapters. Shown at left is an image of the German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer Johannes Kepler, considered one of the important leading figures in the 17th century scientific revolution. Image courtesy The Einstein Website, © Hans-Josef Küpper.

Meanwhile, in the early part of 1609, a comtemporary of Galileo was making his own mark on science. In that year a German named Johannes Kepler published a work under the title New Astronomy, and within its pages were Kepler's first two laws of planetary motion (the thrid would not arrive until 1618). Over the succeeding years, both men would independantly pursue research (though Kepler's theoretical work at this time was ahead of Galileo's) that would eventual become the foundations that merged much of the scientific knowledge up to that time into modern theoretical and physical astronomy. Who was Johannes Kepler and what were his contribution to science are the subjects of our next chapters. Shown at left is an image of the German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer Johannes Kepler, considered one of the important leading figures in the 17th century scientific revolution. Image courtesy The Einstein Website, © Hans-Josef Küpper.

Next Page

Chapter Three

Dangerous Concept, Dangerous Times: Galileo, Kepler and the Church

Present & Future Historical Bytes

© Legal Copyright Notice:

Unless otherwise stated, all images, screen shots, electronic materials including instructional, software, scripts and web pages referred to herein or incorporated by reference are copyrighted © by A Universe in Time. None of the content herein may be reproduced or copied in any manner from this website without the prior written permission of above indicated copyright holder(s). All images and orginal works of the author(s) used within the above or foregoing web pages are for the sole purpose of information and display at A Universe in Time website and have been used with the kind permission of the respective owner(s).

BACK TO THE TOP