Out of this Universe

AUIT's Monthly Astronomical PublicationFrom the Caves on Earth to a Lunar Journey

"Where the world ceases to be the scene of our personal hopes and wishes, where we face it as free beings admiring,

asking and observing, there we enter the realm of Art and Science" — Albert Einstein, 1879-1955

It was July 4th, 1054 and standing in an open area of the Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, a member of the Anasazi civilization looked towards the heavens and, catching his breath, saw something that hadn't been there before, a new and very bright star on the curtain of the night sky. He probably wondered what great spirit caused the new light to appear and shine so brightly. Returning to an area above the floor of the canyon, he did what came natural to him, he painted the stellar scene on a high rock wall; a bright star, a cresent moon and an open hand in colors such as yellow and red, now faded maroon (image left). Nor was he alone, for the ancient sunwatchers, the Sinagua astronomers, as well as Chinese and Japanese astronomers, also recorded the same supernova of 1054 (now known as the Crab Nebula) which was so bright it was visible even in daylight. The overhang and its images were the subject of a 1999 publishing (Charbonneau et al., 1999 see Ward, 2002) in which the researchers found that this Supernova Glyph comes the closest to depicting the event of 1054, a conclusion based on the fact that no other wall paintings were as astronomically convincing as that at Chaco Canyon. Image: Anasazi, Chaco Supernova from Jack M. Barrack Hebrew Academy. [1] fn1

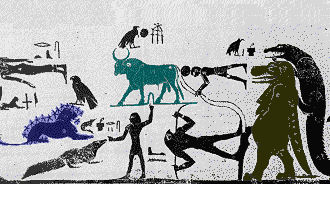

It was July 4th, 1054 and standing in an open area of the Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, a member of the Anasazi civilization looked towards the heavens and, catching his breath, saw something that hadn't been there before, a new and very bright star on the curtain of the night sky. He probably wondered what great spirit caused the new light to appear and shine so brightly. Returning to an area above the floor of the canyon, he did what came natural to him, he painted the stellar scene on a high rock wall; a bright star, a cresent moon and an open hand in colors such as yellow and red, now faded maroon (image left). Nor was he alone, for the ancient sunwatchers, the Sinagua astronomers, as well as Chinese and Japanese astronomers, also recorded the same supernova of 1054 (now known as the Crab Nebula) which was so bright it was visible even in daylight. The overhang and its images were the subject of a 1999 publishing (Charbonneau et al., 1999 see Ward, 2002) in which the researchers found that this Supernova Glyph comes the closest to depicting the event of 1054, a conclusion based on the fact that no other wall paintings were as astronomically convincing as that at Chaco Canyon. Image: Anasazi, Chaco Supernova from Jack M. Barrack Hebrew Academy. [1] fn1 Whether it was the cave paintings of early man, the zodiac figures imaged by Roman artists, engravings from the ancient Egyptians or earlier Greeks (pre—332 BC), the 1500 petroglyphs (rock drawings) at Tanum, astronomy in Hindu mythology or images drawn by Europeans voyaging Polynesian waters, looking up towards the heavens and drawing what one sees has gone hand-in-hand throughout time. And while drawing for purely scientific purposes began early on, it wasn't till the advent of the telescope that things really began to change — artistically speaking that is. Seen at right is an astronomical drawing from the period of Seti I. "Mythological figures used in the New Kingdom and thought to represent constellations in the Northern sky are usually the Hippopotamus, the Bull/Bull's Thigh, the Lion, various crocodiles, and sometimes two male figures, one with a hawk's head, and a female goddess." from The Lion (Leo) was known in the New Kingdom by Robert G. Bauval. [2]

Whether it was the cave paintings of early man, the zodiac figures imaged by Roman artists, engravings from the ancient Egyptians or earlier Greeks (pre—332 BC), the 1500 petroglyphs (rock drawings) at Tanum, astronomy in Hindu mythology or images drawn by Europeans voyaging Polynesian waters, looking up towards the heavens and drawing what one sees has gone hand-in-hand throughout time. And while drawing for purely scientific purposes began early on, it wasn't till the advent of the telescope that things really began to change — artistically speaking that is. Seen at right is an astronomical drawing from the period of Seti I. "Mythological figures used in the New Kingdom and thought to represent constellations in the Northern sky are usually the Hippopotamus, the Bull/Bull's Thigh, the Lion, various crocodiles, and sometimes two male figures, one with a hawk's head, and a female goddess." from The Lion (Leo) was known in the New Kingdom by Robert G. Bauval. [2] The first "scientific based" illustrations of a solar system object began with the arrival of the telescope in the early 1600s, with illustrations of the moon rendered via the medium of pen and paper by Thomas Harriot and Galileo Galilei; not until the advent of Louis Daguerre's camera of 1839 would this change. Kepler and Galileo and later, John Bevis, William Parsons and William Herschel, as well as a multitude of others through the late 1800s, would all draw what they saw through their telescopes and many of our now famous objects were first viewed and named based on the early work of these astronomers and their scientific renderings. At left is a drawing from Galileo, a sketch from his book Sidereus Nuncius (Sidereal Messenger) from 1610, in which he describes the contours of the moon as seen through his newly invented telescope. [3]

The first "scientific based" illustrations of a solar system object began with the arrival of the telescope in the early 1600s, with illustrations of the moon rendered via the medium of pen and paper by Thomas Harriot and Galileo Galilei; not until the advent of Louis Daguerre's camera of 1839 would this change. Kepler and Galileo and later, John Bevis, William Parsons and William Herschel, as well as a multitude of others through the late 1800s, would all draw what they saw through their telescopes and many of our now famous objects were first viewed and named based on the early work of these astronomers and their scientific renderings. At left is a drawing from Galileo, a sketch from his book Sidereus Nuncius (Sidereal Messenger) from 1610, in which he describes the contours of the moon as seen through his newly invented telescope. [3]From the Earth to the Moon in 1865

After the arrival of the telescope, illustrations still remained limited to the science of pure research or to the various flights of imagination, depicting the stellar realm in a most allegorical manner, relying less on science than on the mysticism of the time. But in 1865, that all changed. Drawing on the best scientific knowledge of the day, including the services of selenographers Beer and Maedlerm, Verne's novel From the Earth to the Moon (1865) not only presented his own roughly calculated flight into space but also featured the first true artwork with an eye to scientific reality. As noted by artist and author Ron Miller,

After the arrival of the telescope, illustrations still remained limited to the science of pure research or to the various flights of imagination, depicting the stellar realm in a most allegorical manner, relying less on science than on the mysticism of the time. But in 1865, that all changed. Drawing on the best scientific knowledge of the day, including the services of selenographers Beer and Maedlerm, Verne's novel From the Earth to the Moon (1865) not only presented his own roughly calculated flight into space but also featured the first true artwork with an eye to scientific reality. As noted by artist and author Ron Miller,"The first space art appeared in 1865 with the illustrations by Emile Bayard and A. de Neuvill for Jules Verne's novel, From the Earth to the Moon. There had been imaginary views of other worlds, and even of space flight before this. But until Verne's book appeared, these views all had been heavily colored by mysticism rather than science." [4]

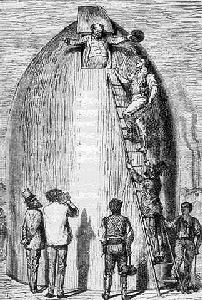

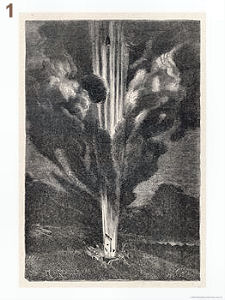

At right is "The Projectile" from Jules Verne's novel From the Earth to the Moon, which was illustrated by Henri de Montaut. The novel is a humorous science fantasy, written in 1865, that actually has similarities to the real-life Apollo program of 1961—1975. "The story is also notable in that Verne attempted to do some rough calculations as to the requirements for the cannon and, considering the total lack of any data on the subject at the time, some of his figures are surprisingly close to reality." Wikipedia

Fig.1 Illustrator Henri de Montaut's (1840—1905) image of the moon-projectile as it shoots away from the earth (From the Earth to the Moon). Montaut was a successful magazine cartoonist who also specialized in portraits—as in his rendering of the three Vernian astronauts Barbicane, Nicholls, and Michel Ardan in Verne's novel (p.284)

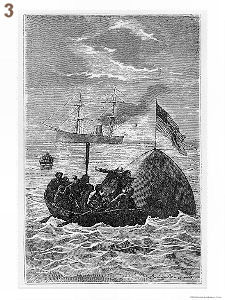

Fig.1 Illustrator Henri de Montaut's (1840—1905) image of the moon-projectile as it shoots away from the earth (From the Earth to the Moon). Montaut was a successful magazine cartoonist who also specialized in portraits—as in his rendering of the three Vernian astronauts Barbicane, Nicholls, and Michel Ardan in Verne's novel (p.284)Fig.2 & 3 Illustrator Émile-Antoine Bayard's (1837—1891) 'Leaving for the Moon' and after, the 'Splashdown' of the projectile in the ocean from Verne's sequel, Around the Moon. It was written of Bayard's illustrative work, "His engravings showing the effects of weightlessness upon the pioneer astronauts; the survey of the moon's surface; and, above all, the 'spashdown' picture are among science fiction's most famous illustrations (#33). The latter piece, showing the American flag securely fixed above the module, proved to be amazingly prophetic when Frank Borman of the Apollo 9 moon expedition landed in the Pacific, one hundred years later, only two or three miles from the point mentioned in the book." [5], [6]

These were the images that began a new era of artistic interpetation and illustration of space and the universe, an art based on the science at hand rather than conjecture or vague, groundless speculation. It pictured the substance of the cosmos via a more scientifically realistic format than had been done previously, eventually bringing together the world of astronomical science and stellar art and in turn, lending itself to the visulaization of our universe in a most gifted, prophetic and meaningful manner.

Footnotes

1. The cave drawing in Chaco Canyon, while still open to interpetation, is not the only evidence found for early inhabitants of this area having recorded the supernova event of 1054. See for example, Supernova Of 1054 AD. The Crab Nebula Archaeoastronomy, Site Of The Earliest Observation Known To Man. This site saw several surveys made with star charts depicting the sky as it would have been viewed in 1054. The results have thus far been remarkable. For more information and a virtual tour the Chaco Canyon site see the NASA sponsored website Traditions of the Sun : Ancient Astronomy

It has been one hundred and forty-four years since the publishing of Verne's From the Earth to the Moon — a period long enough for Space Art to have developed and carved its own niche within the larger field of art in general. Its historical longevity is such that one can readily find written many excellent essays and studies regarding its inception, historical roots and developement, present day form and style, as well as biographies written about the lives and images of those to whom we memorialize as having been its creators.

It has been one hundred and forty-four years since the publishing of Verne's From the Earth to the Moon — a period long enough for Space Art to have developed and carved its own niche within the larger field of art in general. Its historical longevity is such that one can readily find written many excellent essays and studies regarding its inception, historical roots and developement, present day form and style, as well as biographies written about the lives and images of those to whom we memorialize as having been its creators.

As to my own efforts in this area, they are not borne of any particular influence or style, but result largely from the study of astronomy, a lifelong artistic ability ad libitum and a desire to enhance upon the the science renderings one often views at many institutions of science, like NASA, the ESO and others. Some are rendered with the physics of the science in mind and others, simply because they "appear" within the realm of possibility. One need only study and compare examples of such stellar objects as the massive M17 complex, NGC 2174, the Eight Burst Nebula or the Ant Nebula (Mz3), shown above, to understand that nature's own diversity is unbounded, rendering the cosmos in such immeasurable diversity of form that it seems impossible that we will ever be able to create the definitive image of the universe. Above left is an image entitled Stellar Winds Clear a Solar Vista, created by the author in 2008. Images above right are courtesy the

As to my own efforts in this area, they are not borne of any particular influence or style, but result largely from the study of astronomy, a lifelong artistic ability ad libitum and a desire to enhance upon the the science renderings one often views at many institutions of science, like NASA, the ESO and others. Some are rendered with the physics of the science in mind and others, simply because they "appear" within the realm of possibility. One need only study and compare examples of such stellar objects as the massive M17 complex, NGC 2174, the Eight Burst Nebula or the Ant Nebula (Mz3), shown above, to understand that nature's own diversity is unbounded, rendering the cosmos in such immeasurable diversity of form that it seems impossible that we will ever be able to create the definitive image of the universe. Above left is an image entitled Stellar Winds Clear a Solar Vista, created by the author in 2008. Images above right are courtesy the  Space or Astro Art is a relatively new branch within the genre and it gradually developed into several rather distinct styles with different agendas: one created for the world of science fiction and another for the scientific community that required an accurate rendering of objects within our solar system and beyond. When these artistic paths eventually coalesced, it created more than just a new art form, it inspired and gave birth to a generation of writers, artists, engineers, astronomers, scientists and everyday citizen whom came to believe in the very real possibilities of space travel.

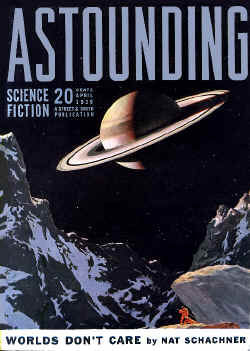

Space or Astro Art is a relatively new branch within the genre and it gradually developed into several rather distinct styles with different agendas: one created for the world of science fiction and another for the scientific community that required an accurate rendering of objects within our solar system and beyond. When these artistic paths eventually coalesced, it created more than just a new art form, it inspired and gave birth to a generation of writers, artists, engineers, astronomers, scientists and everyday citizen whom came to believe in the very real possibilities of space travel. Seen above is the April 1939 issue of Astounding Science Fiction magazine. The cover's artwork was by

Seen above is the April 1939 issue of Astounding Science Fiction magazine. The cover's artwork was by

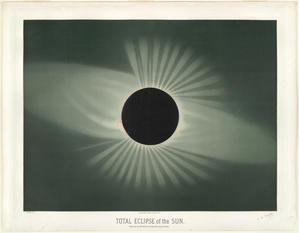

Howard Butler became the first president and founder of the

Howard Butler became the first president and founder of the  Then, at the age of sixty-two, Butler was invited to join a U.S. Naval Observatory expedition to Oregon to chronicle the solar eclipse of June 8, 1918. "As a portrait painter," he wrote in Natural History ("Painting Eclipses and Lunar Landscapes," July-August 1926), "I generally asked for ten sittings of two hours each. But all the time they would allow me on this occasion was 112 1/10 seconds." His finished painting eventually found itself gracing the Hayden Planetarium's rotunda. At left is Butler's painting of the Oregon, June 8, 1918 eclipse which was part of a triptych or three paneled framed display for the "Proposed Hall of Astronomy at the American Museum of Natural History." Notes

Then, at the age of sixty-two, Butler was invited to join a U.S. Naval Observatory expedition to Oregon to chronicle the solar eclipse of June 8, 1918. "As a portrait painter," he wrote in Natural History ("Painting Eclipses and Lunar Landscapes," July-August 1926), "I generally asked for ten sittings of two hours each. But all the time they would allow me on this occasion was 112 1/10 seconds." His finished painting eventually found itself gracing the Hayden Planetarium's rotunda. At left is Butler's painting of the Oregon, June 8, 1918 eclipse which was part of a triptych or three paneled framed display for the "Proposed Hall of Astronomy at the American Museum of Natural History." Notes  In 2000, the

In 2000, the  As both artist and astronomer who authored many famous paintings of space themes in the 1920s and 1930s, Rudaux is most famous and recognized for the collection of scientific drawings found in the definitive Larousse Encyclopedia of Astronomy, which remains an often listed and

As both artist and astronomer who authored many famous paintings of space themes in the 1920s and 1930s, Rudaux is most famous and recognized for the collection of scientific drawings found in the definitive Larousse Encyclopedia of Astronomy, which remains an often listed and  "The catalyst for Schneeman's interest in science fiction and drawing was explained in a letter written to Alva Rogers: 'a friend showed me an early copy of Amazing Stories sometime in 1927 and it was my undoing. The world lost a chemist as I went down the science fiction drain. Early artistic influences included Winsor McKay, Franklyn Booth, McClelland Barclay and H.G. Wesso.' " Charles Schneeman began illustrating for Astounding Stories in 1935. His first cover illustration for Astounding Science Fiction appeared in May 1938 and he continued illustrations for the magazine through 1952. Schneeman passed away on January 1, 1972 and a great portion of his records and work is currently cataloged at the

"The catalyst for Schneeman's interest in science fiction and drawing was explained in a letter written to Alva Rogers: 'a friend showed me an early copy of Amazing Stories sometime in 1927 and it was my undoing. The world lost a chemist as I went down the science fiction drain. Early artistic influences included Winsor McKay, Franklyn Booth, McClelland Barclay and H.G. Wesso.' " Charles Schneeman began illustrating for Astounding Stories in 1935. His first cover illustration for Astounding Science Fiction appeared in May 1938 and he continued illustrations for the magazine through 1952. Schneeman passed away on January 1, 1972 and a great portion of his records and work is currently cataloged at the